Coursework: Multimodal Translation

- AudiovisualCourseworkEntertainmentPortfolioSubtitling

Table of Contents

Intro

This was my favourite assignment and focussed on accessible audiovisual translation, specifically audio descriptions, theatre subtitling and then film subtitling.

It was certainly eye opening (heh) to see how translation decisions are made when it comes to accessibility. In this context, translation doesn’t refer to just between languages, but also translation within the same language, such as between spoken and written formats.

Subtitles in particular have a large array of constraints applied to them, most notably character/word limits per second on screen, number of lines, how to identify speakers, how to handle Non Speech Information (NSI)—particularly useful for Subtitles for the Deaf or Hard of Hearing (SDH)—and so on.

Through my studies, I also learned that it is not quite as simple as accepted practice based on the scientific method. Various studios (we looked at a couple, including the BBC and Netflix) have different approaches to translation with different quantifiable rules and constraints.

One thing that is often neglected is the fact that content of the subtitle can impact the viewers average read time, depending on how predictable or complex it is.

For example, if the line includes filler words that your brain easily skips over, those words shouldn’t be included in a character-per-second count. On the other hand, a technical term in a documentary might require double the reading time as your brain has to work out what it’s reading. Additionally, convoluted word play might require the watcher to double back and reread passages, which again can increase reading time.

As these factors require individual judgement calls, they tend to be overlooked and/or frowned upon in style guides, although many also pad-out or apply scales to their various limits so there is at least some wiggle room for the subtitler, although this is not always the case.

Looney Tunes

It so happened that when the examination portion of the module came a-knocking, I had been going through a box-set of the old Looney Tunes cartoons (I’m partial to bugs bunny).

For a lark, I turned on the subtitles to see what Warner Bros had done with them, only to be horrified by what I found—lacklustre, sparse and in some cases just missing, it was barely worth them having been included at all. I know the boxset was put together in 2009, but still.

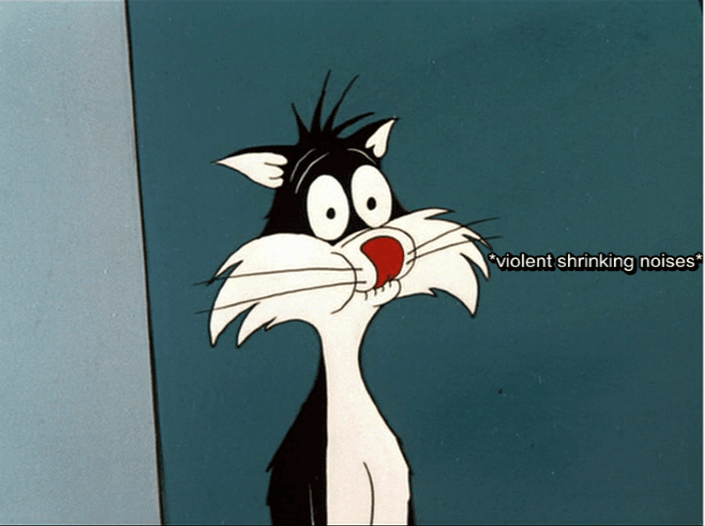

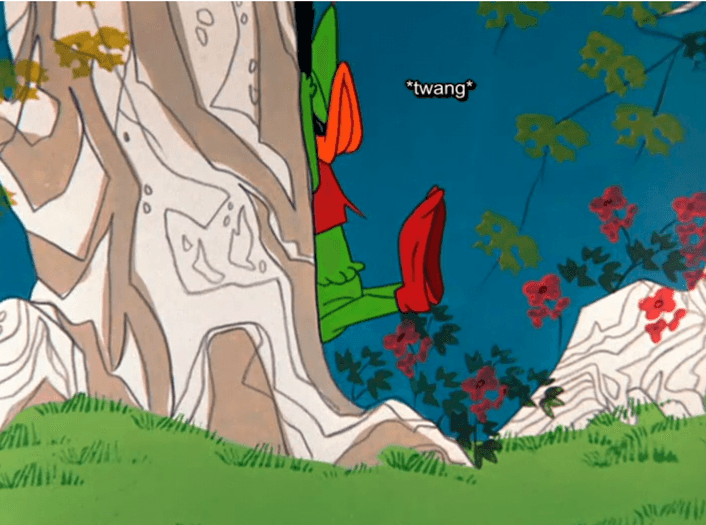

Knowing what I now knew about subtitling and particularly SDH, I decided I could do better and so I went about applying SDH to two shorts, Birds Anonymous and Robin Hood Daffy, with the aim of including the important NSI information and structure it “creatively”.

In this case, that meant placing static subtitles in different parts of the screen in line with where the sound “originated”, which is different from the standard 1-2 lines you usually see at the bottom of the screen (although I did research on how to apply moving or animated subtitles as well, just in case).

It so happened that when the examination portion of the module came a-knocking, I had been going through a box-set of the old Looney Tunes cartoons (I’m partial to bugs bunny).

For a lark, I turned on the subtitles to see what Warner Bros had done with them, only to be horrified by what I found—lacklustre, sparse and in some cases just missing, it was barely worth them having been included at all. I know the boxset was put together in 2009, but still.

Knowing what I now knew about subtitling and particularly SDH, I decided I could do better and so I went about applying SDH to two shorts, Birds Anonymous and Robin Hood Daffy, with the aim of including the important NSI information and structure it “creatively”.

In this case, that meant placing static subtitles in different parts of the screen in line with where the sound “originated”, which is different from the standard 1-2 lines you usually see at the bottom of the screen (although I did research on how to apply moving or animated subtitles as well, just in case).

Creative SDH

The assignment was to produce SDH, either “normal” or “creative” as you saw fit, and to then justify the decisions you made and the challenges you came across. (Pretty standard stuff by this point).

The biggest issue I had to deal with was that visual dialogue, unlike audio dialogue, happens linearly, meaning one after the other rather than at the same time as part of a unified soundscape. This forces you then, especially when subtitling NSI, to set a hierarchy of sounds, deciding what needs to be included for comprehension, and then what needs to be left out so that the screen doesn’t become cluttered or confusing.

Deciding what information to include and in what priority order are the largest challenges besides technical constraints to anyone producing SDH and, to a lesser extent, hearing subtitles as well when it comes to, for example, multiple speakers or long, fast sections of dialogue where you just don’t have the room to include everything.

The Human Eye

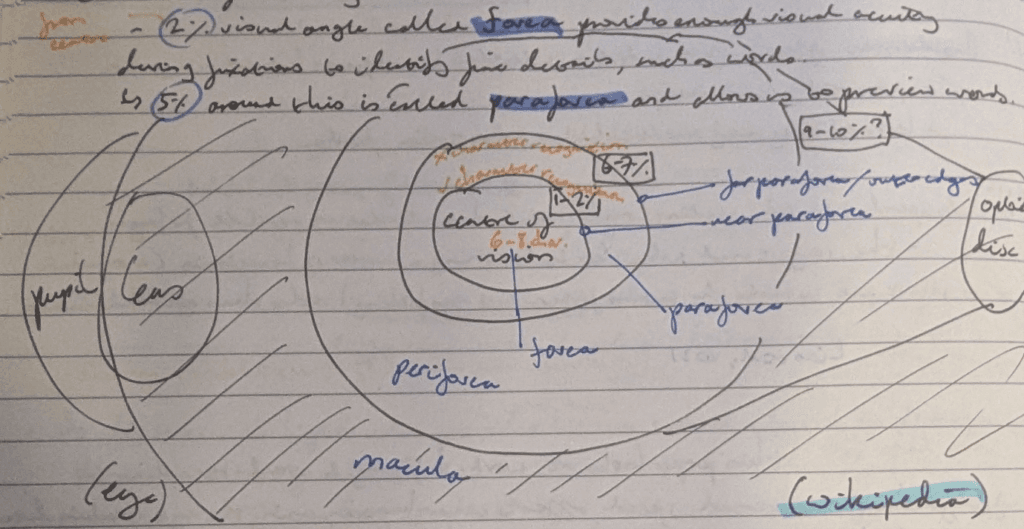

I will admit, I overdid this project. I went so far as to research how the human eye worked and how humans process visual information—particularly words—to counter some of the questions I had about why there was so much deviation in accepted word and character limits, as the other data I had access to focussed on the effect and not the cause. Really, it is quite remarkable just how much biology and neuroscience plays a part in our ability as a species to process written language.

As you can see from my notes (sorry for my horrendous handwriting), I did use Wikipedia but that was actually to dumb down the diagram and information I was otherwise copying from. If you want to read more about psycholinguistics (which is a cool thing I now know exists), the paper in question was J.L. Kuger et al’s (2022) “Why Subtitle Speed Matters: Evidence from Word Skipping and Rereading,” in the journal Applied Psycholinguistics (43:1, pp.211-236) available on www.cambridge.org.

To give you a summary, humans pre-read characters that appear in their 3-5% viewing angle, and fully read the words in their 1-2% viewing angle, skewed towards your reading direction (so if you read left-to-right, you focus your outer ring of perception on the right-hand string of characters). You also use your peripheral vision (along with some serious chicanery from your brain—human vision is a total neurological scam) to keep an eye (heh) on what you’ve already read.

So, for English, you keep your eye on about 6-8 characters to the right of the point you’re fixating on, and can see maybe 3-6 characters either side of that section, while simultaneously staying cognisant of words further to the left that your brain lies to you about being able to actually still see.

As the human brain also likes to—essentially—utilise predictive text when it reads, characters you “preview” to the right help your brain work out whether you already know what the next word is going to be. If it’s sure of its guess, you won’t actually fixate on the next word, and instead skip over it. If the string then doesn’t conform to the “prediction” later on, you’re more likely to go reread what you’ve “misread” (although you didn’t…actually read 20-30% of it).

Additionally, we tend to reread while not realising that we’re rereading, especially with longer or faster dialogue segments where there is more uncertainty/information to process—but anyway, this was a great rabbit hole to go down and it suggested that Netflix’s character-per-second limit (12-20cps) could be extended a little bit, as 30% of the study’s participants could read faster than that limit.

Conclusion

Despite all my research and learning how to use a bunch of new software, the principle behind this project was not complicated. It revolved around simplicity. At the end of the day, whether you like to or have to use subtitles, you don’t want to have to stress over them.

Coincidentally, I found a 2005 study by Ofcom, “Subtitling—An Issue of Speed?”, which surmised that viewers will typically get frustrated quickly when their cognitive load is increased unnecessarily and will turn off a programme rather than battle through overly complicated or cluttered subtitles.

Finding ways to limit that cognitive load while still remaining true to the dialogue or NSI, be it of the same or different language, is the subtitler’s job, even if that requires taking some liberties which would normally be frowned upon in written-written translation.

Thankfully, the Looney Tunes shorts didn’t have long monologues that would’ve required condensing, but it did—as from the pictures above—have a lot of NSI that I had to succinctly convey in such a way that it didn’t stress out or distract the watcher.

In a future project and some more time/study, I would work on integrating the subtitles into the animation by animating them as well. For this project however, I focussed on positioning and timing so that they would naturally fall where the viewer was already looking, or would drag the viewer’s attention to a section of the screen in the same way that the sound information would.

(If you would like to watch the shorts, I still have them up on DropBox. You can view Daffy here, and Sylvester here.

Otherwise, if you want to push through yet more rambling, you can read my essay here).

Image credits: all me

- All Posts

- Blog

- Portfolio

- Back

- Public Authorities

- Tourism

- Antiques

- General Medical

- Quality Control

- Translation

- Coursework

- Paid

- Voluntary

- Business

- Games Industry

- Machine Translation

- Post Editing

- Theory

- Baking

- Recipes

- Literary

- General Legal

- Subtitling

- Audiovisual

- Transcribing

- Entertainment

- Professional Development

- Back

- Rate mal!