Driving Licences

- Driving LicencesOfficial DocumentsPortfolio

Table of Contents

Intro

Translation is a varied profession. Alongside translating creative works to transport their voice to a new audience, or slogging your way through technical manuals with or without machine assistance, we may also be asked to translate official documents, such as certificates, identity documents, copies of invoices, references, or any kind of document that can be used for or issued in an official capacity.

This was the case for me recently with a driving licence, something I technically knew how to do but had yet to actually attempt, and I was surprised by the depth of the task (and grateful now to have done all the research to make this a repeatable feat).

Having spent quite a bit of time on it, I decided I would write up the experience, both to show to potential clients what the process and end-product looks like but to also provide a how-to guide for erstwhile translators who are just dipping their toes into these professional waters!

※ It’s important to note here that you CANNOT translate your own driving licence, as most if not all countries will not accept it.

Translating Official Documents

First to consider are official documents in the general sense.

The biggest challenge is not necessarily the content on the page as—such as in the case of a driving licence which we’re looking at here —there aren’t many words to actually ‘translate’. What we’re instead doing is making a document issued under one cultural context—with its own laws, stipulations, requirements, standards, etc etc—and making them usable, and above that, understandable in another.

You could say that translating official documents is cultural translation, rather than linguistic.

In this way, it almost has to be very obvious that what you’re producing is a translation. If you try and produce a document that is legally binding or usable in its own right, then there are extra steps, extra professionals that you have to get involved and, honestly, it would be better in many cases to create that document from scratch in the target culture than necessarily translate it.

Hence, translated official documents are typically supporting documents to any particular endeavour…

…including making a new official document in the target culture (such as having a new driving licence issued in a foreign country you’ve migrated to).

Here, though, your job is to inform and provide utility. You don’t try and interpret, there is no real room for subjective interjection (such as with a marketing text), you don’t judge (it’s other people’s job to do that).

If something is unclear or illegible, you include that in your translation rather than trying to guess. You can add notes or cultural explanations as to what X symbol, code, law, reference etc pertains to (and, often, in contrast to how things are done in the target culture) but use extreme care and objectivity so you don’t misrepresent the parties relying on you.

At the end of the day, you’re explaining what that document is and showing what it contains, in other words: a documentary translation.

The formula I was taught for translating official documents and may help you here is this:

- Translator’s opening

- what is the document; what is the original language

- what is the purpose of the document; why is it being translated

- who supplied it, how; where is it going, etc

- The contents of the document, with illegibility/ unclear segments (such as a bad signature) and translator’s comments marked in [ ] square brackets.

- You may also want to include a translator’s summary if something in particular needs substantial explanation

- Translator’s closing/ declaration with certification and/or other legal elements (such as legalisation or notarisation by a notary public as it is done in the UK).

A demonstration of this can be seen in the example translation I’ve created and linked at the bottom of the article. The following sections, likewise, dive into this a bit deeper by looking at a German driving licence as an example.

German Driving Licences

Modern German driving licences follow a European standard. UK driving licences, in contrast, only partially reflect this standard, so although they appear similar, some of the elements (such as vehicle classifications or, even, just the lettering for the same classifications, can be different). American ones have their own system entirely.

This is important to know as when picking apart the licence, the information supplied on them may not be obvious at first glance because they follow different rules than their counterpart in the target culture. This is why including a summary alongside the translation is important in this case as you can clarify what, exactly, the licence allows the holder to drive.

Below is a breakdown of a German licence using a diagram I drew for this purpose.

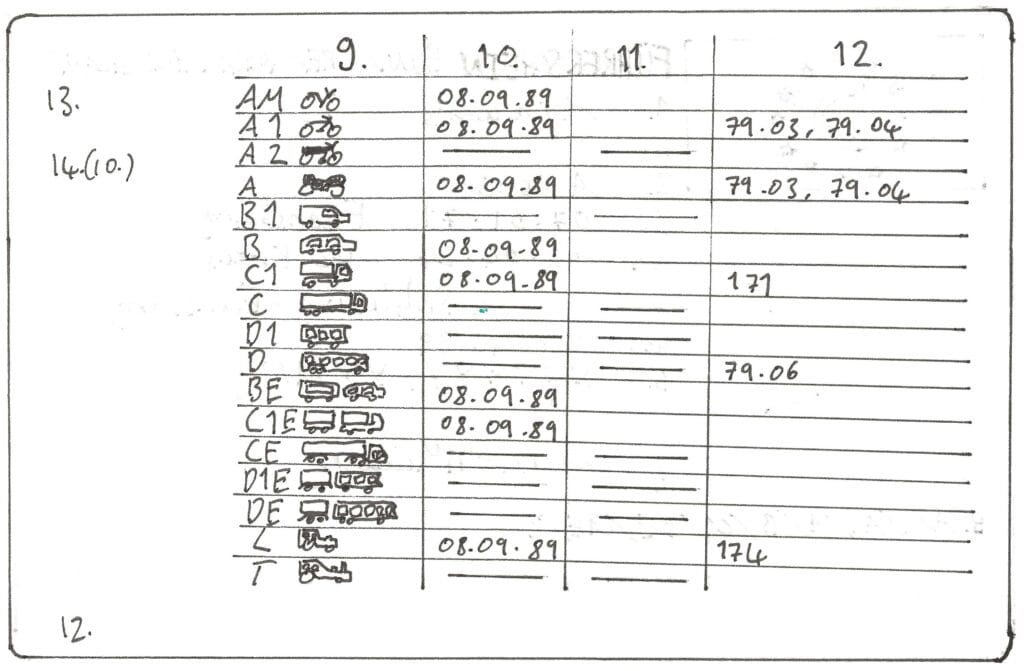

※ Additionally, Germany switched to card licences in 1999, and then to the European format/classifications in 2013, with the aim being to phase out all old licence types by 2033. This is important as it explains many of the amendments to the classifications that you’ll see on a converted licence compared to a fresh one, which is what I spent most of my time researching most recently. (You can read more about the switch in English here, on the BMV’s website).

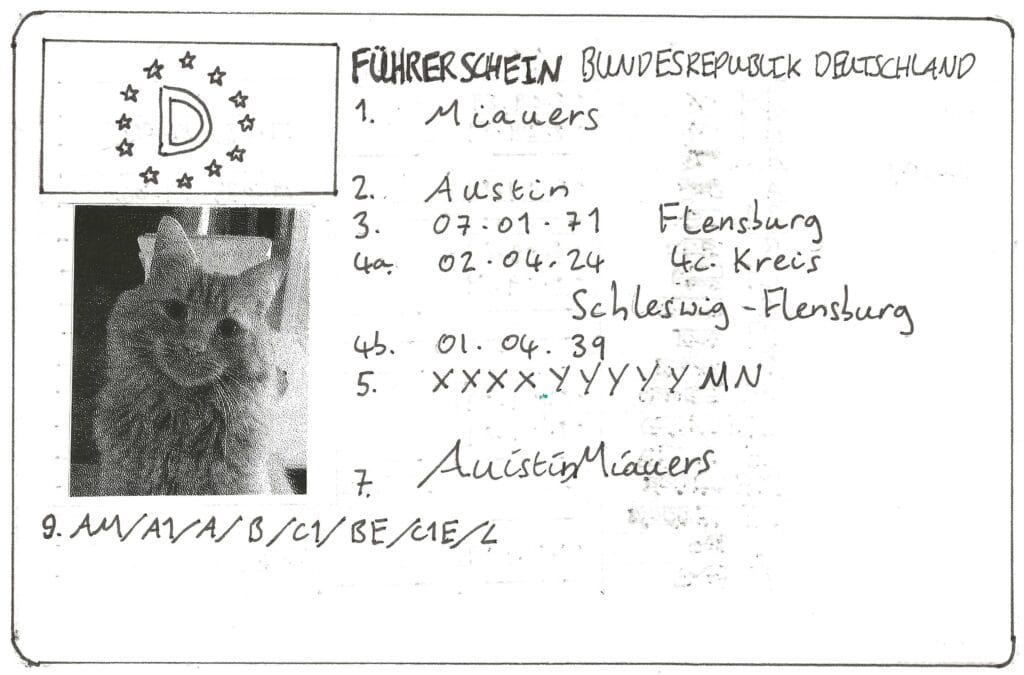

For the purposes of this article, I created a licence for my cat, Austin. (For anyone who missed the pun, my family often refer to him as Austin Meowers, a reference to Austin Powers, spoof spy of mystery, and then I just…wrote “meow” in German. Hey, at least I make myself giggle).

Obviously, my cat Austin is not 56 years old (wouldn’t that be impressive?). He’s actually around 7. I chose these dates to better reflect some of the restrictions (section 12 in the graph below) that you might find when encountering reissued, older licences.

On the licence, you can also see the EU flag with the D for Deutschland. For the sake of thoroughness, I included a [ ] bracketed ‘translation’ of this element. Likewise, in your opening it should be noted that the translation is of a driving licence issued in Germany. The main focus though really is the numbered elements, as seen in the table below.

| 1. | [Surname] | Miauers |

| 2. | [Given name(s)] | Austin |

| 3. | [Date and place of birth] | 07.01.71 [7th January 1971], Flensburg |

| 4a. | [Date of issue] | 02.04.24 [2nd April 2024] |

| 4b. | [Expiry date] | 01.04.39 [1st April 2039] |

| 4c. | [Issuing authority] | District of Schleswig-Flensburg |

| 5. | [License number] | XXXXYYYYYMN |

| 7. | [Signature] | Austin Miauers |

| 9. | [Categories] | AM/A1/A/B/C1/BE/C1E/L |

| 10. | [Valid from] | 08.09.89 [8th September 1989] (all classes) |

| 12. | [Restrictions / additional information] | A1/A: 79.03, 79.04. C1: 171. BE: 79.06. L: 174. |

Note also that these have been written in order, rather than trying to emulate the format of the licence itself. This is so the information is as easy to follow as possible; additionally, as a documentary-style translation, retaining the original’s format isn’t (often) necessary as long as the contents are accurate.

Something else I’ll quickly explain here is the German licence number: you’ll hopefully notice that I’ve created a blatantly fake one for this demonstration.

The German licence number is broken into four sections: the four-digit code for the issuing authority of the licence (XXXX), the five-digit alphanumeric code for the licence (YYYYY), the one-digit proof code (M) and the one-digit issue number (N).

The licence number always starts with a letter corresponding with the state in which it was issued. The rest of the Xs further refine that into the specific region in that state.

The Ys in contrast indicate the nth licence produced by that issuing body, where letters are used to substitute for larger numbers. Suffice it to say, each issuing authority in Germany can produce up to 60.4 million different licences…

The M is then a “proof” number where the X and Y codes are multiplied by 9-1 consecutively and then divided by 11. The (rounded to 1) decimal point value is then “M”. If you end up with an equal number without any decimal values, then the M is written as an actual “X”.

… Let’s just call this “funky maths” and move on, ey?

Finally, the N is the nth copy of this particular licence. I for example have passed two motorcycle tests and so have had two licences issued, so if mine were a German licence, it would end in “2”.

You wouldn’t think that it was important to understand this, but when I recently stumbled over an O, thinking it was a 0, this knowledge helped me recognise which was which (otherwise I would have made a rather horrible mistake). So…the more you know.

Issuing Authorities

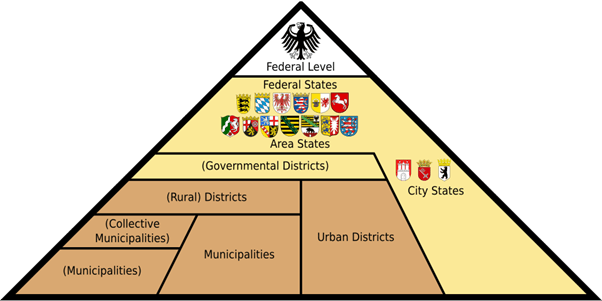

In column 4c, you’ll notice the “issuing authority” of the licence. In the UK, this is always the DVLA but in Germany, this is the local authority of the region in which the licence was obtained.

On starting this project, I decided to research some examples to better see what was expected. (A formula is one thing, an example is another). This also gave me the idea to create my own…

While doing so, I stumbled across an interesting translation choice: “Municipality of Gifhorn”.

In German, this would the Landkreis Gifhorn, very similar to the Kreis Schleswig-Flensburg in our example. Annoyingly, though, when researching the administrative structure of Germany to double check how these bodies were defined, I found something troubling: they weren’t municipalities.

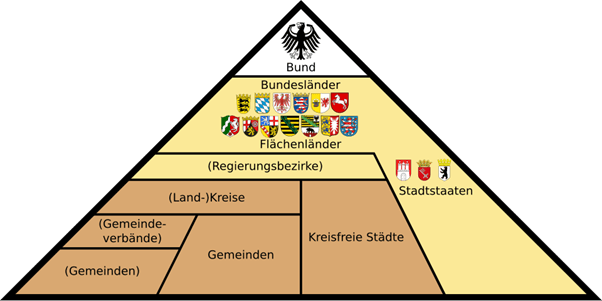

A municipality in Germany—a Gemeinde—is one of the smallest administrative bodies going, whereas a district (Kreis or Landkreis) is bigger, with independent cities (administratively speaking) known as kreisfreie Städte [lit. “district-less”, although in the diagram below: “urban districts”], which can both be the size of a municipality or a district.

Was this a translation error? A synonym of “district”, defying the other prominent translations online, such as the websites of the local governments in question?

In the UK, likewise, we have counties and districts (alongside metropolitan boroughs) but no longer have “municipalities,” so what was going on??

Then I had a forehead slap moment. Of coooooourse. What about in America?

※ It’s always America (*continues to grumble in irritated British*).

Indeed, local government in America is made up of (broadly speaking) counties and…..municipalities! A rough comparison would mean that Gifhorn, seen through an American lens, is a municipality. But that’s only if we’re shoving it into an American local government system, which, really, we’re not.

Then again, “municipality” and “district” are both relative to the countries that define them, so perhaps for someone going to America and having their licence translated, that makes the most sense?

Personally, I’ll stick with “district,” thank you, as that seems to be the translation that the German local government bodies have opted for. Who knew I would ever opt for a foreignising translation strategy? Venuti would be proud.

Cultural Summaries

Let us return to the task, and the example, at hand.

As different countries have different classifications of vehicles, their sizes and weights, it’s important to ‘translate’ this also. The way I see it is if a police officer asks someone for their licence and sees a bunch of letters they’re not familiar with, they’re either going to act with the (lack of) information at hand or spend ages looking that information up.

Thus, by including this information on the translation, you’re providing a point of commonality with which to compare the source-culture licence with a target-culture one. You could, perhaps, even go so far as listing what classifications the licence caters for in the target culture. With my most recent job, it was neglected to inform me what English-speaking area the translation was needed for, so I didn’t bother with this, instead focussing on listing the vehicles the licence allows one to drive. (This is also why the dates are also written out in full rather than just numerically).

There were two ways for me to approach this:

- To translate the classifications and following that, the additional amendments (column 12). Here is a PDF, in German, breaking down all the categories and additional codes, provided by the district of Lindau. You could, theoretically, translate this entire document and then copy and paste the sections as you need them.

- Create a summary with the relevant information, thus saving space and condensing what is ultimately a rather convoluted amount of information if the individual letters and numbers don’t concern you (which is what I opted for).

※ The option you choose may also depend on the target culture in question. Foreign licence holders may have different, blanket restrictions applied to them or the specific restrictions on the licence may be partially ignored, otherwise they will refer to your specific licence and not the local classifications. This will be discussed further in the next section.

To give you an example, let’s see if I can break down the German classifications without confusing…well, myself, really.

Broadly speaking…

- A is for motorbikes and the like,

- B is for cars/ light passenger vehicles,

- C is for medium-large transport vehicles and

- D is for medium-large passenger vehicles.

…all with or without trailers and different weights—or more specifically, Maximum Authorised Mass (MAM), Permissible Maximum Weight (PMW) or Gross Vehicle Weight (GVW); in German: zulässige Gesamtmasse (zG or zGM), which includes that vehicle’s weight plus anything it might be carrying while on the road.

Additionally,

- L and T allow you to drive agricultural (farming and forestry) vehicles, such as tractors, forklifts and other specialist vehicles, on the road. The former is smaller/slower, the latter is larger/faster.

Then we come to the number codes (oh joy). Using the ones on Austin’s licence, this is where things get tricky, and why I spent an hour going back and forth between the lettered classifications and numbered codes.

Somehow, it probably would have been easier to just go with option 1 and let some poor civil servant do this, but here we are…

Codes…

- 03 and 79.04 both concern motorcycles; namely, you’re allowed to drive trikes with a small trailer, but not motorbikes. This is because of the old licence types, where a car licence included trikes, whereas nowadays you need a motorbike licence instead and it doesn’t include the trailer.

- 171 lets you drive a medium-sized passenger truck as if it were a medium-sized transport truck, in other words: with a load but without passengers.

- 06 lets you drive a car with a trailer that is over 3500kg MAM.

- 174 relates to class L: with newer licences, this class restricts you to driving specialist vehicles for agricultural purposes only, but this wasn’t so with the old licence types, so code 174 essentially removes this restriction, allowing you to drive tractors and other specialist vehicles not related to agriculture.

Finally, for this example, I have to point out classification “C1E” as this intersects with both the other classifications and the codes above: namely, Austin can drive light-medium sized passenger and transport trucks with a trailer that adds up to a whopping…12,000kg MAM. Yikes.

※ To explain my initial confusion, I will blame the trailers. Class B lets you—with a car—have trailers up to 750kg, but Class BE raises that to 3500kg. Then, code 79.06 lets you have trailers over that limit, and then finally, Class C1E establishes the new limit of 12,000kg combined. So I ended up having to (re)write the summary four times.

This is the summary that I wrote for Austin’s licence:

Categories of vehicles covered by this license:

Category A (motorcycles) | Only three-wheeled motorcycles; includes a trailer with maximum authorised mass (MAM) of no more than 750kg. |

Category B (cars) | Passenger vehicles for up to 8 persons and a MAM of 3500kg; includes vehicle and trailer combination with a MAM of no more than 12,000kg. |

Category C (medium-sized vehicles) | Medium-sized vehicles with a MAM of 3500-7500kg; includes medium-sized passenger vehicles (more than 8 persons) with a MAM no higher than 7500kg and without passengers; includes vehicle and trailer combination that doesn’t exceed a MAM of 12,000kg. |

Category L (tractors and specialised vehicles) | Forestry or agricultural tractors up to 40km/h, or 25km/h with trailer; industrial/lift trucks (specialist vehicles, forklifts) up to 25km/h; includes other specialist vehicles constructed to only go to a maximum speed of 40km/h; with single-axel trailers (where axels less than a metre apart count as a single axel), up to 25km/h. |

When do you need a translation?

Whether you’ll need a translation of your driving licence depends on what you’re using it for and where you are; if you plan to drive, you need to make sure you’ve made the appropriate provisions.

For example, when I was preparing to move to Japan (where I lived for a year), I ended up going to the local Post Office in the UK, where I could get an International Driving Permit (IDP). It cost me about £5 (currently £5.50) and required a pre-prepared passport photo. This may not be the case for every country, depending on whether or not they accept IDPs.

※ The UK, Germany, Japan and the US will all issue IDPs to their own residents and accept them from tourists.

If you want to drive in the UK from abroad…

- If you’re driving in the UK using a foreign licence, then there are some caveats:

- If you have a licence issued in Europe or the European Economic Area, then you’ll be able to drive without issue using your licence. Just make sure you have proof of insurance or get insured while in the UK.

- If you have a licence issued outside of the designated countries, then you can drive small vehicles (motorbikes and cars, as per your own licence) for 12 months from when you entered the country. If you’re licenced to and have driven a lorry or bus into the country, then you may continue to drive that vehicle but no other large vehicles.

- If your licence is written in another language (other than English and Welsh) or with different lettering, then you will either need an International Driving Permit (IDP) or a certified translation.

- You can check here (gov.uk) to see what you might need.

If you want to drive in America from abroad…

- Then this depends on the state(s) you are going to. Broadly speaking, you can drive in the US with your licence plus an IDP for up to one year, but the specific rules change per state. Your best bet is to prepare an IDP, your licence and a translation if not in English. Check with your embassy in the US or the travel advisories for the states you want to visit to determine what you need.

If you want to drive in Germany from abroad…

- An IDP is certainly useful but not a requirement (as long as you’re coming from the EEA). As long as you are over 18, you can drive in Germany with a valid licence for an unlimited period.

- If you’re coming from outside the EU/EEA, you will need an IDP or a translation of your licence and if you move to Germany (from the UK for example), then you will have to obtain a German licence within 6 months (excluding students).

- There are special provisions for the driving of C and D class lorries/trucks, mainly concerning age (over the age of 50, you must have clearance from a doctor to drive large vehicles) and you can only drive them for 5 years from the issuing date, regardless of the rules in the issuing country.

- You can find out more from the BMV.

If you want to drive in Japan from abroad…

- You must either have an IDP or a translation of your licence. These are only valid for one year since entering Japan and you may be required to show your passport alongside your licence and IDP, if asked. After the one year, you may no longer drive unless you leave the country for 3 months before re-entering. Otherwise, you will need to obtain a Japanese licence.

- A bunch of countries, including the US, UK and Germany, have agreements with Japan to smoothen the process of acquiring a Japanese licence. You will have to have a Japanese translation of your licence however, and this will need to be issued by accepted institutions such as the Japanese Automobile Federation (JAF), the German Automobile Federation or your relevant embassy in Japan, alongside a bunch of other documents. You can read more on this here (japanlivingguide.com).

You may also need your licence translated if…

- You plan to use your licence as legal ID verification

- Applying to rent a home or for use with any other kind of contract where a passport does not suffice

- Insurance claims

- Applying for asylum

- Exchanging a foreign licence for a local one

Certification

Certification is common practice with a lot of official documents, but what this means depends on where you are in the world. In the UK and US, for instance, certification is as simple as the translator including a declaration that the translation is as correct as can be, and that includes their contact information, signed and dated.

In the UK, this declaration must include the words “true and accurate translation of the original document” as per the GOV UK rules. Some third-party institutions such as the ITI or CIOL in the UK, ATA in America, NAATI in Australia, etc, can accredit a translator, lending weight to your certifications by providing you stamps that you can include along with your certification. In fact, some countries/institutions will only accept certified translations from an accredited translator.

In Germany, however, “certification” is done by a ‘sworn translator’, a role that exists in many civil law countries, including France, Spain, Italy, etc, where the translator has to be ‘sworn in’ by their local courts.

In the UK, though, you’d have to have your translation legalised/apostilled, where your declaration is signed by a Notary Public; further, you can have the document notarised, where the Notary Public includes their own declaration. In this way, the document can become legally binding in its own right. (However, it is important to note that a legal professional who is also a translator cannot legalise or notarise their own translations. Also, it’s unlikely you’ll need such a service for a driving licence—typically, this is more for contracts and the like).

※ Interestingly, I am a “certified translator” in that I have a Masters in Translation Studies (i.e., a certificate), but I am not yet an “accredited translator” and cannot become one for another 4+ years (you have to have 5 years in the industry, be able to supply references and proof of words translated, and complete a practical test, if I remember correctly). Unfortunately, I cannot become a “sworn translator” as my home base is in the UK.

This is an example of a blank certification that I created:

Translator’s Declaration

I, [full name], [accreditations/ certifications/ etc], do declare that this is a true and accurate translation of the original document, to the best of my knowledge and ability. The source document was supplied to me as a [specific format].

| LOGO/ STAMP | [full name] [phone number] [website] [email] [address, etc] | ||

| SIGNED: | DATED: | ||

This is essentially for the purposes of accountability rather than providing any legal weight to a document. If there is an issue, such as a mistranslation or, worse, an intentional change or omission (whether that has been requested by a client or done solely by the translator for whatever reasons), this ensures that they will have to take their share of responsibility.

This is why it’s important in a lot of cases—such as a signature on a driving licence—to note if and when it’s unintelligible, or if there’s a typo, etc, rather than extrapolating information from the source text and ‘changing’ the target text, just in case this becomes an issue later and then it’s your neck on the block.

※This is also why liability insurance exists.

Conclusion

I hope this article has once again demonstrated that translation isn’t quite as simple as it looks on the tin. There are a lot of different elements you have to consider and research, even for the most mundane things.

Should anyone wish, I have compiled my example translation into a PDF—formatting it in order to better demonstrate some of the points above—and you’re welcome to use this to create a template for yourself, should it work for your language pair and the target culture’s requirements.

You can access that here: EXAMPLE DE-EN Driving Licence Austin Miauers.pdf.

Until the next time!

K

Image credits: me; me again; Wikipeda

- All Posts

- Blog

- Portfolio

- Back

- Public Authorities

- Tourism

- Antiques

- General Medical

- Quality Control

- Translation

- Coursework

- Paid

- Voluntary

- Business

- Games Industry

- Machine Translation

- Post Editing

- Theory

- Baking

- Recipes

- Literary

- General Legal

- Subtitling

- Audiovisual

- Transcribing

- Entertainment

- Professional Development

- Official Documents

- Driving Licences

- Boardgames

- Back

- Rate mal!